Teaching a Graph of Knowledge as a Story

I have the chance to teach several courses: computer graphics, CUDA programming, and machine learning. One of the main difficulties I constantly run into is that the content of these courses does not form a linear sequence. Instead, it forms a graph of knowledge.

This is especially true for machine learning. The field evolves quickly, new ideas appear constantly, and many concepts depend on each other in non-trivial ways. There is no obvious “Chapter 1 → Chapter 2 → Chapter 3” path that feels natural or complete. CUDA programming is no different: it assumes parallel thinking long before students have fully developed it. Computer graphics is no better, as it requires understanding the full pipeline that produces an image on a computer before knowing how and why each part works.

And yet, teaching happens in time. Slides advance one after the other, and lectures unfold sequentially. Teaching is linear by necessity. This tension, between a graph of concepts and a linear presentation, is at the core of how I think about teaching. The question, then, is not whether we impose a linear order, but how.

Modern technical education often assumes that knowledge can be cleanly reduced to outlines, tables of contents, and dependency trees. If the structure is correct, the thinking will follow, or so the assumption goes. This idea is not new. It can be traced back at least to Petrus Ramus, who believed that all knowledge should be reduced to orderly diagrams and linear schematics. His influence is still visible today: chapters, subsections, bullet points, and curricula that promise clarity through structure alone.

But there has always been another tradition. Ramon Llull, and others like him, understood that humans do not learn primarily by traversing diagrams. They learn through stories, images, and meaning, even when the underlying structure is complex.

This way of thinking also connects naturally to the idea of threshold concepts [1][2] in education: concepts that, once understood, fundamentally transform how a student sees a subject. I think the insights I try to create are a sort of threshold concepts. Threshold concepts are often troublesome, irreversible, and integrative; they reorganize the mental landscape rather than adding another node to it. The advantage of a threshold concept is that, when you finally grasp it, you cannot ever forget or unsee it. In my experience, many of the hardest moments for students occur precisely when they are approaching such thresholds. A strictly structural or chapter-driven approach tends to hide these moments, while a narrative, insight-driven approach can bring them to the foreground.

I sometimes refer to this approach as insight-based teaching. It is not opposed to structure, but it does not start from it. It is influenced by my view on inquiry-based learning, in the sense that understanding is built through exploration, questioning, and reframing, rather than through passive traversal of a predefined outline. The structure emerges after the insight, not before.

Why I Don’t Teach Strictly by Chapters

I do have chapters. I do have sections. But they are not the backbone of my courses. Instead, the core structure follows something closer to a story. Ideas are introduced when they become meaningful, not necessarily when they would be considered “correct” according to a strict table of contents.

In my slides, I focus on maintaining a clear linear path of understanding, without relying on future knowledge to make sense of the present. This warps the underlying graph in unexpected ways and can sometimes look like unstructured content. But make no mistake: this does not mean the material is unstructured.

On the contrary, I put a great deal of effort into linearizing the concepts, arranging them in an order that makes the story feel coherent, causal, and logical, even if that order does not match the true structure of the conceptual graph. I prioritize insights over formal structure. The goal is that, at any given moment, students feel that what comes next makes sense given what they already know, and that at each step, they should understand why the next idea appears.

This is where I consciously diverge from the Ramist impulse to reduce everything to schematic order. Structure matters, but it should serve understanding, not replace it.

A Parallel with How Mathematics Is Often Taught

This way of teaching is not as unusual as it may seem. In many universities, pure mathematics has long been taught in a similar spirit. A lecturer may enter the room without slides, start with a question or a mathematical object, and then proceed by exploring its properties, constraints, and consequences. The lecture unfolds as an investigation rather than as the execution of a prewritten script.

In such settings, the direction of the lecture often depends on what students ask, what confuses them, and which paths seem worth following. The structure is not fully specified in advance. The implicit chapter might be “we should understand this object”, but the exact route, and sometimes even the intermediate results, are not always known beforehand. What matters is that the object is explored thoroughly and meaningfully by the end.

This style of teaching is inherently unstructured in appearance, yet deeply structured in intent. Its coherence does not come from a predefined list of topics, but from the internal logic of the mathematical object itself. The exploration continues until the object has been seen from enough angles to become stable in the students’ minds.

Once this global map has been built, later and more advanced lectures can afford to focus on specific parts of it. At that point, the teaching can become more technical, more specialized, and sometimes even drier. But this dryness is no longer a problem: the underlying structure is already understood, the key insights are in place, and new details have somewhere to attach. Precision can replace exploration precisely because exploration has already done its job.

Another characteristic of this exploratory style is how prerequisites are handled. While investigating an object, it may become clear that students are missing some necessary background. Rather than treating this as a failure of preparation, the lecture naturally opens a parenthesis: the missing concept is introduced on the spot, just deeply enough to allow the exploration to continue. This detour is itself exploratory, motivated by an immediate need rather than by an abstract curriculum requirement.

A good example of this approach can be seen in Po-Shen Loh’s lectures (American IMO coach) on discrete mathematics, such as his CMU course, Loh, an American IMO coach, regularly pauses the main line of exploration to develop just enough background for the argument to move forward. These moments are not digressions; they are integral to the process. The prerequisite is learned because it is needed, and its purpose becomes immediately clear. This style is one of the reasons his teaching, both in lectures and through platforms like Expii, is so widely appreciated by students.

My own approach is strongly influenced by this tradition, even if the medium is different. I prefer using slides not because I want tighter control over content, but because I do not want students to spend their time transcribing what I say. Slides allow them to focus on the ideas as they unfold, while providing carefully designed figures and notation that would be cumbersome to recreate by hand.

Despite the presence of slides, I try to teach as if the lecture were an exploration. The sequence is guided, but not rigid. The goal is not to cover a checklist of results, but to investigate an idea until it becomes clear. In that sense, the slides act less as a script and more as a shared workspace: a place where questions, visualizations, and partial insights can accumulate and connect.

This is also why the content of a “chapter” is not always fully determined in advance. From time to time, I add verbal or blackboard explorations in response to students’ questions. What must be explored is known; how that exploration unfolds depends on the students, the questions that arise, and the conceptual obstacles encountered along the way. As long as the object has been genuinely explored, the chapter has done its job.

The Necessary Strain of Learning

This approach inevitably creates some strain for students. They are not used to material that is not presented strictly as a table of contents. When they study, they need to revisit the material and form their own structure, one that, at that point, begins to resemble the true underlying graph. This is demanding work.

But even if I followed a strict table-of-contents path, that strain would exist anyway. If I strictly followed chapters and subsections, the same problems would appear: chapters would constantly refer to material further ahead in the course, or assume background knowledge students do not yet fully have. The strain is unavoidable, the question is whether it is meaningful.

I believe it is. Learning is not passive consumption, it is active reconstruction. One of the most important parts of learning is the student’s own work of restructuring knowledge into something that makes sense to them. That effort, reorganizing, connecting, revisiting, is where real understanding forms.

Once concepts have been understood through a linear narrative, it becomes much easier to mentally reconstruct the original graph: to move freely between ideas, to apply them out of order, and to form higher-level insights. But that reconstruction must happen internally. No outline can do it for them.

Why Books Often Feel Hard to Follow

If students want pure reference material, they can easily pick a book; many excellent ones are freely available. Books often present knowledge closer to its graph structure, supported by a table of contents. In machine learning, I often see three recurring patterns, usually mixed together.

The first is the grand overview: a long introductory chapter that covers the entire field in a hand-wavy way, followed by chapters that zoom into details while silently assuming the introduction is now fully internalized. The reader is expected to rework those initial concepts in the context of later chapters, a task that is difficult and often one students are reluctant to undertake.

The second is the assumed background. Books freely use tools like convex optimization, probability theory, or linear algebra, assuming readers have seen them before, without making those assumptions explicit. While it is understandable that authors cannot explain everything for every audience, it is unlikely that the author’s background and the student’s background align closely enough for this to work seamlessly.

The third is the forward-reference loop. Chapters repeatedly refer to concepts “explained later,” forcing the reader to constantly jump ahead or trust that things will eventually make sense. This requires continuous mental bookmarking and frequent back-and-forth through the material.

None of these approaches are wrong. But they require significant effort from the reader, and they are often difficult precisely because they expose the graph of knowledge directly. The strain on the student would be there anyway, just in a different form.

Reconstructing a Graph, Not the Graph

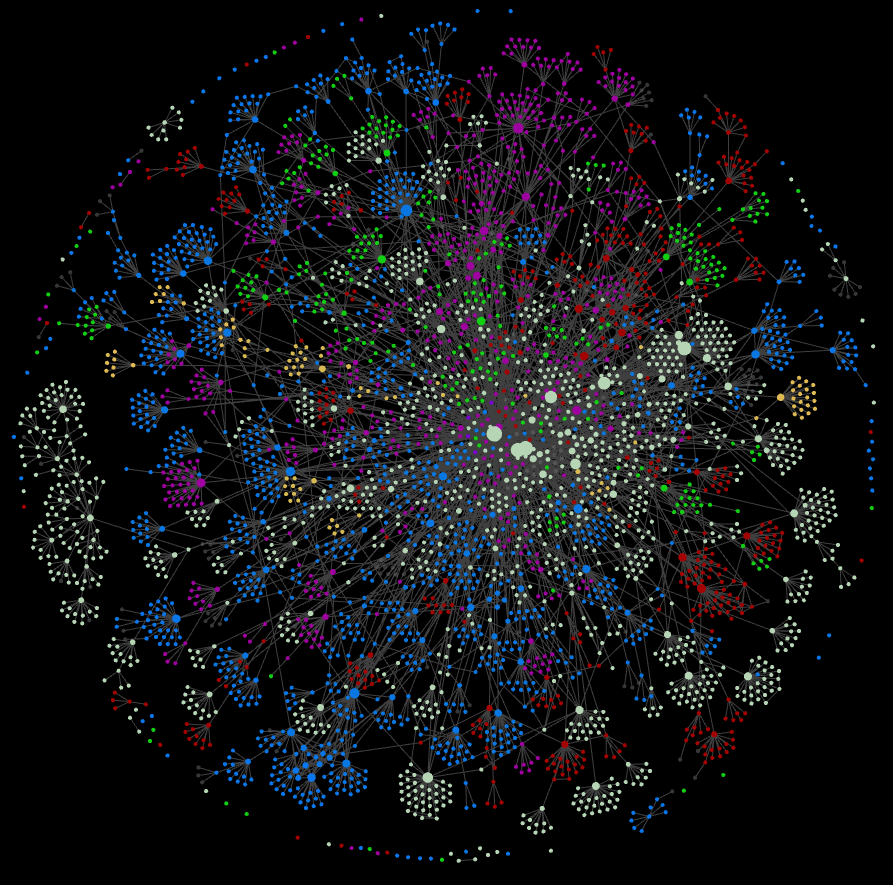

Over time, I have seen several students independently adopt tools like Obsidian, often using its knowledge graph view to organize their notes. What matters to me is not the tool itself, but what it reveals about how understanding evolves.

These graphs do not mirror the underlying structure of the material. They are the student’s own graph: partial, uneven, sometimes messy, and constantly evolving. And that is precisely the point.

A beginner typically experiences a subject linearly. Concepts arrive one after another, and understanding is local: “this follows that”. As learning progresses, that linear view slowly breaks down. Ideas begin to connect across lectures, across chapters, and sometimes across courses. The material stops feeling like a path and starts feeling like a space.

I believe that reaching this stage is a strong marker of real understanding. A true expert does not hold a subject as a sequence, but as a richly interconnected graph of ideas. From that graph, one can see not only what is known, but also what is missing: gaps in understanding, weak connections, and unexplored paths. Questions arise naturally from the structure itself.

Graph-based note-taking tools make this transition visible. They externalize a process that normally happens only in the mind: the gradual construction of a personal knowledge graph. The goal is not to match some canonical structure, but to build a coherent internal model that can be navigated flexibly.

In that sense, the linear narrative of a course is a temporary scaffold. Mastery begins when students no longer rely on that scaffold, and can move freely within their own graph; seeing connections, noticing absences, and extending the structure as new ideas are encountered.

My Teaching Goal

I know that reference material exists, and I want students to be able to use it effectively. My focus, however, is different. I aim to provide core insights: the main ideas that make everything else click once students encounter it again in a book or a paper. I want them to build mental images, intuitions, and internal structure.

That is why I teach more like a story than like a table of contents. If students walk away with the right insights, then when they later read material that is denser, drier, and more complete (as reference material often must be), it suddenly becomes clear. The formulas stop being symbols on a page and start representing something meaningful. Those well-interconnected core insights form the beginning of their internal graph, which they can expand with other lectures and references.

This does ask something of the students: they need to reorganize the material for themselves, even if I try to make that as easy as possible. But that effort is not a drawback, it is the point.

My purpose as a teacher is to teach, not to throw a book at students and ask them to recite parts of it. Teaching, to me, is not about transmitting a perfectly ordered diagram of knowledge. It is about guiding students toward understanding. Otherwise, what would be the point of universities, if one could simply read enough books?

I find my time, and theirs, best spent when I give core insights that come from experience and long engagement with the material, insights that are not readily accessible in the books. Not because they are absent from books, but because they are often buried beneath layers of formalism.

One important difference today, compared to even a few years ago, is that students are no longer alone when trying to reconstruct structure. In the age of large language models (LLMs), students can actively interrogate the material: asking questions about slides, requesting alternative explanations, generating plots to explore how equations behave, or testing “what happens if” variations that would have been tedious to do by hand. Used properly, these tools can help compensate for the lack of an explicit table of contents by supporting exploration and sense-making.

But this only works if students practice the right skills. Asking good questions, forming hypotheses, building and refining mental images, and checking intuition against computation are themselves part of learning. Insight does not come from the tool, it comes from the process. LLMs can accelerate that process, but they cannot replace the internal work of forming understanding.

The Role of Visual Thinking

Finally, I put a lot of effort into figures. Many of the subjects I teach rely on abstract mathematics and symbolic reasoning, and visual representations help anchor these abstractions. They connect formulas to geometry, computation to space, and algorithms to intuition.

This is not aesthetic embellishment. It is a deliberate pedagogical choice, closer to Llull’s illustrated reasoning than to Ramus’s bare schematics. Equations are essential, but without mental images they remain fragile. Visuals help students truly own the concepts, not just manipulate them.

This emphasis on visual and conceptual thinking is not new. It echoes ideas found in works such as Engel’s book on programming mathematics, recently being updated to python, where programming is presented not merely as implementation, but as a way of thinking mathematically, externalizing structure, testing intuition, and refining insight through concrete experimentation. Writing code, drawing figures, and manipulating equations are all ways of thinking, not just producing results.

In that sense, building mental images and insights is a craft. It can be practiced, refined, and taught, even if it cannot be fully reduced to a checklist or syllabus.

In the End

Teaching a graph of knowledge in linear time is inherently difficult. There is no perfect ordering, no universal outline. But I believe that a carefully constructed narrative and embracing intuition, one that respects structure without being dominated by it, helps students do more than follow along. It helps them think.

And once they can think with the material, they can navigate the graph on their own.

References:

- Meyer, J. H. F., & Land, R. (2005). Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knowledge (2): Epistemological Considerations and a Conceptual Framework for Teaching and Learning. Higher Education, 49(3), 373–388. 25068074 (pp. 412-424). Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh.

- Breen, S., & O’Shea, A. (2016). Threshold Concepts and Undergraduate Mathematics Teaching. PRIMUS, 26(9), 837–847. 10.1080/10511970.2016.1191573

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: